On this page

What Is Restrictive Lung Disease?

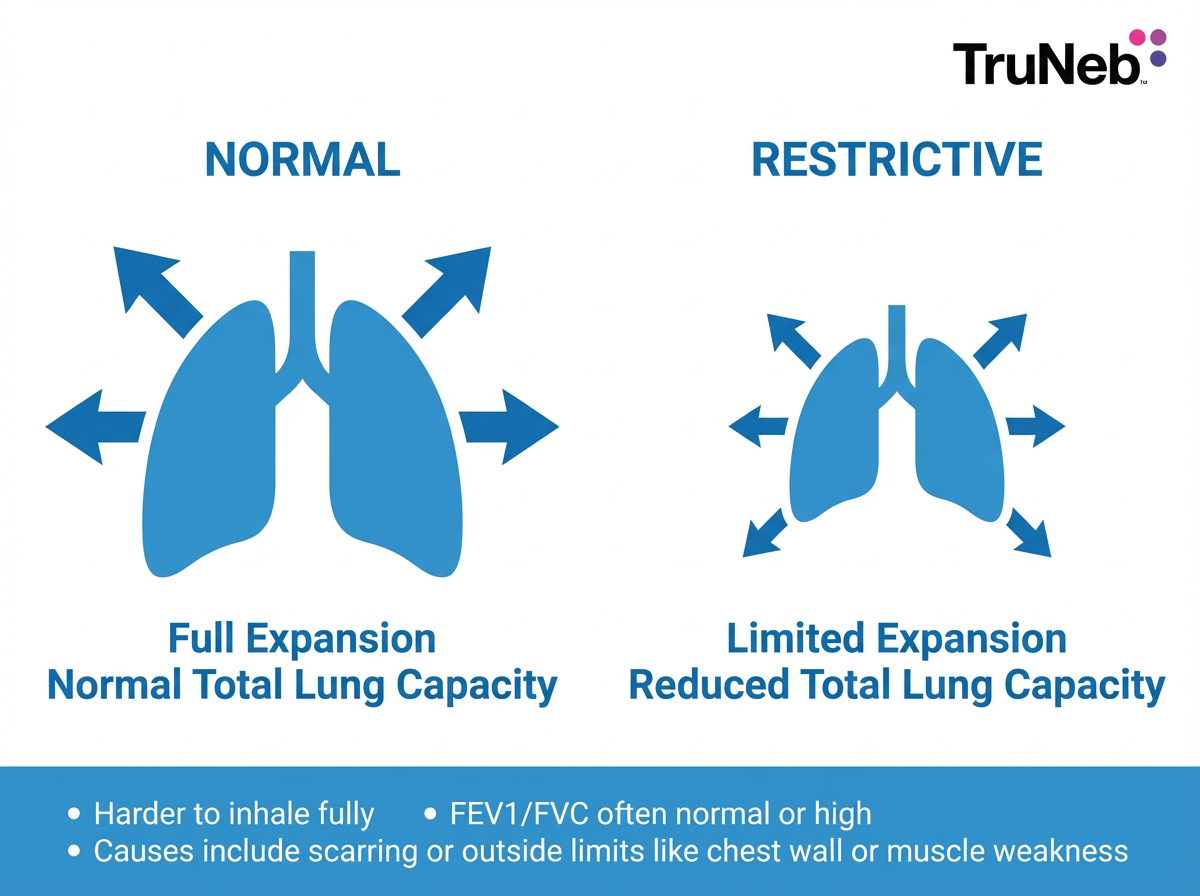

Restrictive lung disease means your lungs can't fully expand, so you take in less air with each breath. The problem is lung volume, not blocked airways.

Think of a stiff balloon. No matter how hard you blow, it won't stretch. That's similar to what breathing with restrictive lung disease can feel like.

This can happen when lung tissue becomes scarred and less elastic, or when something outside the lungs limits chest movement, like a rigid spine or weak breathing muscles. It's different from obstructive diseases such as asthma or COPD, where narrowed airways make it hard to blow air out.

Common examples of restrictive lung disease include conditions that scar the lungs, like pulmonary fibrosis, and problems outside the lungs, like severe obesity or spine curvature.

Doctors confirm a restrictive pattern with breathing tests that show reduced total lung capacity.

Key takeaway: Restrictive lung disease limits how much air your lungs can hold by reducing total lung capacity.

Common Symptoms of Restrictive Lung Disease

Because the lungs don't expand well, oxygen intake drops and breathing can feel tight.

- You might notice shortness of breath when you're active, and sometimes at rest when it's severe

- Rapid, shallow breathing because each breath is small

- Chronic dry cough

- Fatigue and low exercise tolerance

- Chest tightness or a stuck feeling when you try to take a deep breath

Symptoms usually develop gradually but can worsen over time, depending on the cause of the restrictive lung disease.

If these symptoms don't improve or keep getting worse, see your doctor for testing. If you already have a lung or neuromuscular condition and your breathing gets noticeably worse, contact your doctor promptly.

Key takeaway: In restrictive lung disease, breathlessness with activity and a dry cough are the most common early signs.

- Restriction = reduced total lung capacity; FEV1/FVC is usually normal or high.

- Examples span lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) and outside limits (obesity, kyphoscoliosis, neuromuscular disease).

- Diagnosis requires full lung volumes; a low TLC confirms a restrictive pattern.

Source:StatPearls (NCBI).

How Is Restrictive Lung Disease Diagnosed?

Doctors use pulmonary function tests. On spirometry, the forced vital capacity is reduced. With full lung volumes, total lung capacity is below normal, which confirms a restrictive pattern. The FEV1 to FVC ratio is usually normal or even higher because both numbers fall together.

A diffusion test (a test that measures how well oxygen moves from your lungs into your blood) can show reduced gas transfer when scarring is present.

Imaging helps find the cause. Chest X-rays and high-resolution CT scans can show fibrosis, granulomas, or pleural thickening. Blood tests and sometimes a lung biopsy help confirm specific diseases.

A pulmonologist puts these results together to explain the pattern and the cause. Doctors often repeat pulmonary function tests over time to monitor how restrictive lung disease is progressing.

Key takeaway: A low total lung capacity on lung volume testing confirms a restrictive lung disease pattern.

Causes of Restrictive Lung Disease: Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic

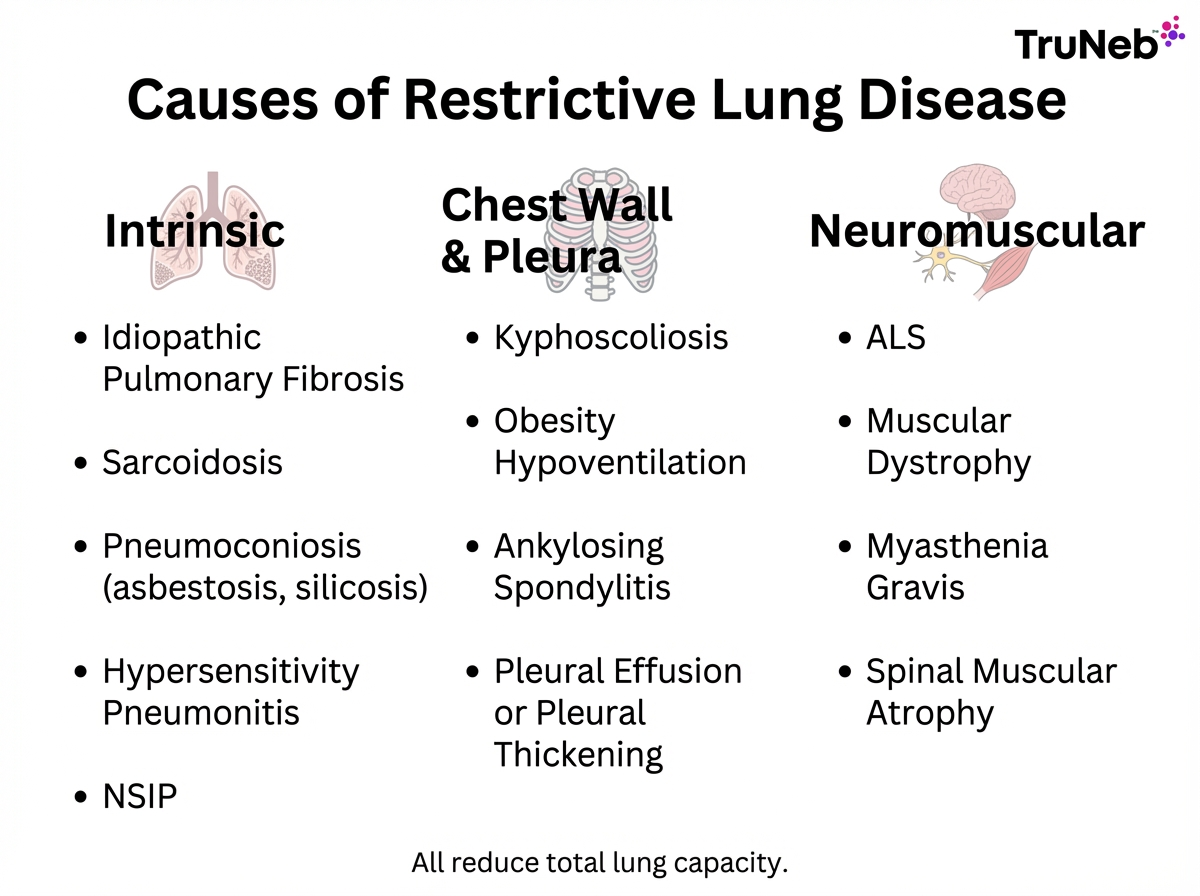

Causes fall into two broad groups.

- Intrinsic causes affect the lungs themselves. These are interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) marked by scarring or inflammation that stiffen lung tissue.

- Extrinsic causes of restrictive lung disease are outside the lungs. These include chest wall or pleural problems and neuromuscular disorders that limit how far the chest can move.

Clinicians sometimes use the acronym PAINT: Pleural, Alveolar, Interstitial, Neuromuscular, and Thoracic cage.

Comparing the main categories of restrictive lung disease: each type reduces total lung capacity in a different way, so treatment targets the specific cause.

| Type | Where the problem is | Typical examples | How breathing is limited | Reversible? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic (interstitial) | Inside the lungs (lung tissue) | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Sarcoidosis, Pneumoconiosis (asbestosis, silicosis), Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis, NSIP/organizing pneumonia | Scarred, stiff alveoli reduce lung stretch and gas exchange | Varies by disease; scarring usually isn't reversible, but early trigger removal or treatment can help some cases |

| Extrinsic (chest wall/pleura) | Outside the lungs | Severe kyphoscoliosis, Obesity hypoventilation, Ankylosing spondylitis, Pleural effusion or pleural thickening | Chest wall and pleura limit how far the lungs can expand | Sometimes; treating the mechanical problem (for example, weight loss or pleural treatment) can improve volumes |

| Neuromuscular | Nerves and muscles that power breathing | ALS, Muscular dystrophy, Myasthenia gravis, Spinal muscular atrophy, High spinal cord injury, Guillain–Barré syndrome | Weak diaphragm and chest muscles reduce inhaled volume | Varies; some conditions improve with therapy (e.g., myasthenia), others are progressive |

Note: Examples are illustrative, not complete. Talk to your doctor for a diagnosis and personalized treatment.

Key takeaway: Restrictive lung diseases are caused either by stiff, scarred lungs on the inside or by limited chest movement from problems outside the lungs.

Intrinsic Causes: Interstitial Lung Diseases and Lung Scarring

These diseases damage lung tissue itself, making the lungs stiff and less stretchy.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

This is a common interstitial disease in older adults that slowly scars the lungs. It leads to a dry cough, worsening shortness of breath, and crackling lung sounds. New antifibrotic drugs can slow decline. Older studies show average survival around three to five years after diagnosis, though outcomes vary, and newer treatments have helped some people live longer.

Sarcoidosis

An inflammatory disease that forms granulomas in the lungs and sometimes other organs. It can reduce lung elasticity and cause a dry cough and breathlessness. Some cases stay mild, but others become long‑term lung problems that need ongoing care.

Pneumoconiosis

Lung scarring from inhaled dusts at work. Asbestosis comes from asbestos exposure, and silicosis from silica dust. Scarring develops over years and doesn't reverse.

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

An immune reaction to inhaled organic particles, like mold or bird proteins. Early removal of the trigger can help and may prevent long-term scarring. This condition is sometimes called 'farmer's lung' or 'bird fancier's lung' depending on the trigger.

Other Interstitial Lung Diseases

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and organizing pneumonia are additional examples, sometimes linked to autoimmune disease.

Key takeaway: Interstitial lung diseases scar lung tissue and are a classic source of restrictive lung disease.

Extrinsic Causes: Chest Wall and Pleural Restrictions

Here, the problem isn't in the lungs themselves — limits outside the lungs physically reduce expansion.

Severe Kyphoscoliosis

A curved spine and rib cage reduce space for the lungs, causing a chronic restrictive deficit. Some people need nighttime ventilatory support as disease advances.

Obesity Hypoventilation

Excess chest and belly weight presses on the diaphragm and chest wall, limiting deep breaths and lowering oxygen. Weight loss can improve or sometimes normalize lung volumes when recommended and supervised by your doctor.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

A form of arthritis that stiffens the spine and rib joints over time, reducing chest wall movement and lung expansion.

Chronic Pleural Disease

Long-standing pleural effusion or thickened pleura, sometimes after infection or surgery, can trap the lung and restrict breathing. These changes can follow infections like tuberculosis, lung surgery, or inflammatory conditions that scar the pleura.

Key takeaway: When a chest wall or pleural problem causing extrinsic restrictive lung disease can be treated, breathing often improves.

Neuromuscular Causes: Weak Breathing Muscles

Here, the lungs can be normal, but the pump is weak. The diaphragm and chest muscles can't pull air in fully.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Progressive nerve loss weakens all muscles, including the diaphragm, leading to chronic ventilatory failure, meaning the body can't move enough air in and out on its own. Many people eventually need ventilatory support.

Muscular Dystrophy

In advanced stages, breathing muscles weaken and scoliosis may add restriction. Nighttime ventilation often helps.

Myasthenia Gravis

Fluctuating muscle weakness can involve the diaphragm. Severe episodes, called crisis, can cause acute breathing failure, but treatment often improves strength.

Other examples include Spinal Muscular Atrophy, high spinal cord injuries, and Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Key takeaway: When breathing muscles are weak, lungs cannot expand, and volumes fall even if lung tissue is healthy.

Treatment and Management of Restrictive Lung Disease

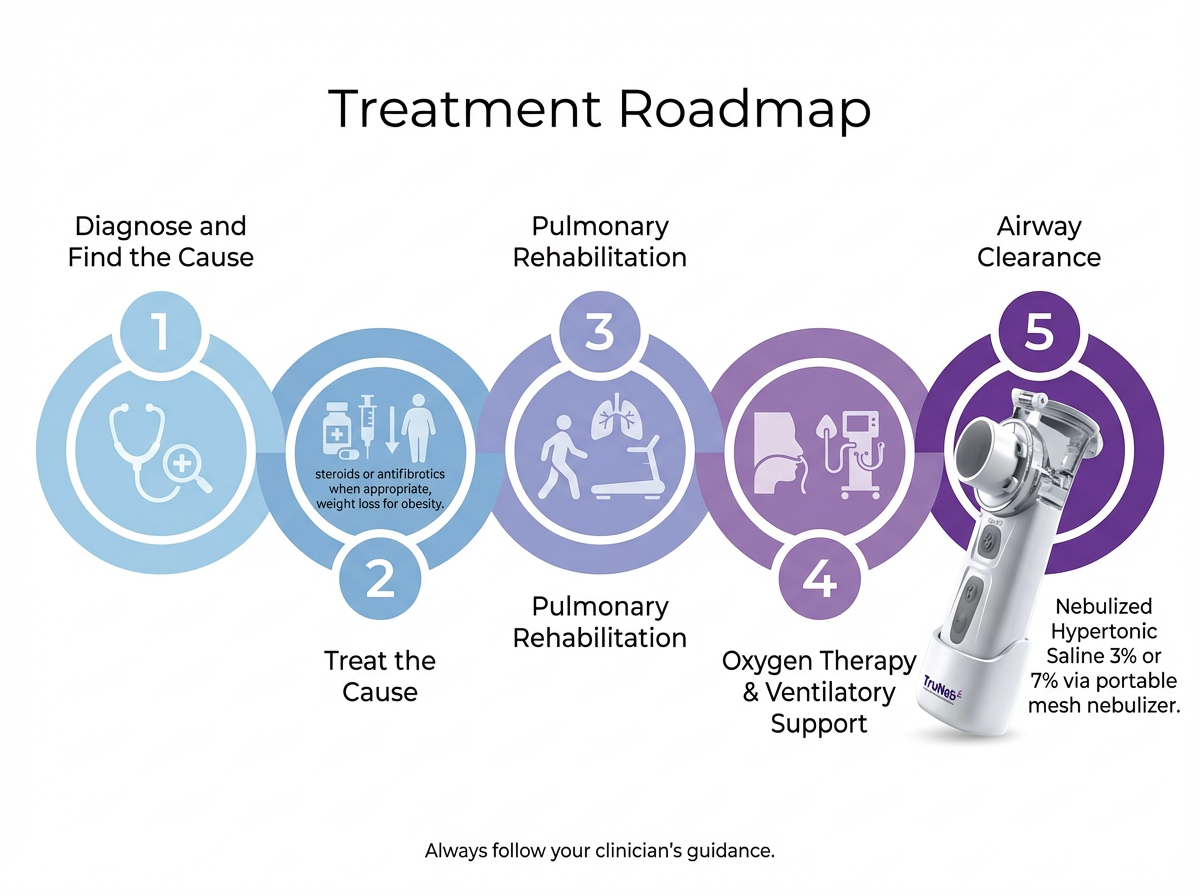

Treatment depends on the cause, and your doctor or lung specialist tailors a care plan to your specific condition.

- Address the cause: Anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive medicines may help certain interstitial diseases like sarcoidosis or organizing pneumonia. Avoid further harmful exposures. For obesity-related restriction, doctors typically recommend sustained weight loss to help improve breathing and lung volumes.

- Disease-specific options: For idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, antifibrotic medicines can slow decline. Lung transplant is an option for select patients with advanced disease. These treatments are prescribed and monitored by specialists.

- Supportive care: Pulmonary rehabilitation improves stamina and daily function. Oxygen therapy helps people whose levels run low. Vaccines for flu and pneumonia lower the risk of setbacks. If you smoke, your doctor will encourage you to quit, because smoking further damages lung tissue and raises the risk of infections.

- Airway clearance: Some people with scarring also deal with thick mucus or repeat infections. A portable mesh nebulizer can deliver 3 percent or 7 percent hypertonic saline to thin and mobilize mucus so it's easier to cough up. Hypertonic saline isn't right for everyone and can irritate the airways in some people, so use it only if your doctor recommends it. Don't substitute a steam inhaler for a nebulizer — steam devices don't deliver medication into your lungs and can cause burns. A compact device like TruNeb is convenient for people who need nebulized treatments at home or while traveling.

- Ventilatory support: In neuromuscular causes or severe chest wall restriction, noninvasive ventilation such as BiPAP at night can ease work of breathing and improve blood gases.

Safety note: Talk to your doctor before trying a new medication or nebulized saline. Don't start or stop any prescription treatment on your own.

Key takeaway: Managing restrictive lung disease means treating the root cause and adding rehab, oxygen, airway clearance, and ventilatory support as needed.

Prognosis and When To See a Doctor

Outlook varies by cause and by how early treatment starts. Some causes are reversible or improve, such as obesity-related restriction after weight loss. Others, like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, tend to progress. Older studies show average survival of about three to five years after diagnosis, though newer treatments have helped some people live longer. Your individual outlook depends on your diagnosis, overall health, and how you respond to treatment, so these numbers are averages, not guarantees.

See a doctor if you notice lasting shortness of breath, a dry cough that doesn't clear, or trouble taking a deep breath. People with spine disease, autoimmune disease, or neuromuscular disorders should have regular lung checks.

If you have sudden severe shortness of breath, chest pain, confusion, or blue lips or face, call emergency services or go to the nearest emergency department right away.

Early evaluation can improve outcomes by targeting the cause and starting supportive care.

Key takeaway: In restrictive lung disease, prognosis depends on the underlying cause, and early care often improves your outlook.

Frequently Asked Questions

Tap or click a question below to see the answer:

Five clear examples are Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Sarcoidosis, Pneumoconiosis such as asbestosis or silicosis, Severe Obesity with Obesity Hypoventilation, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Together they show the range from scarring inside the lungs to outside limits from the chest wall or weak breathing muscles.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is one of the most commonly diagnosed intrinsic restrictive lung diseases in adults. In everyday life, severe obesity is also a very common cause of a restrictive pattern, though it isn't a disease of the lungs themselves.

Asthma is obstructive. It narrows airways and makes it hard to blow air out. In asthma, total lung capacity is usually normal or high, not reduced.

COVID-19 is an infection, not a chronic lung disease. Severe COVID can make lungs stiff in the short term and can leave scarring after recovery, which behaves like a restrictive lung disease. It isn't an obstructive disease like asthma or COPD.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always talk to your doctor about your symptoms, test results, and treatment options.