On this page

Understanding RSV and Why It Causes Breathing Problems

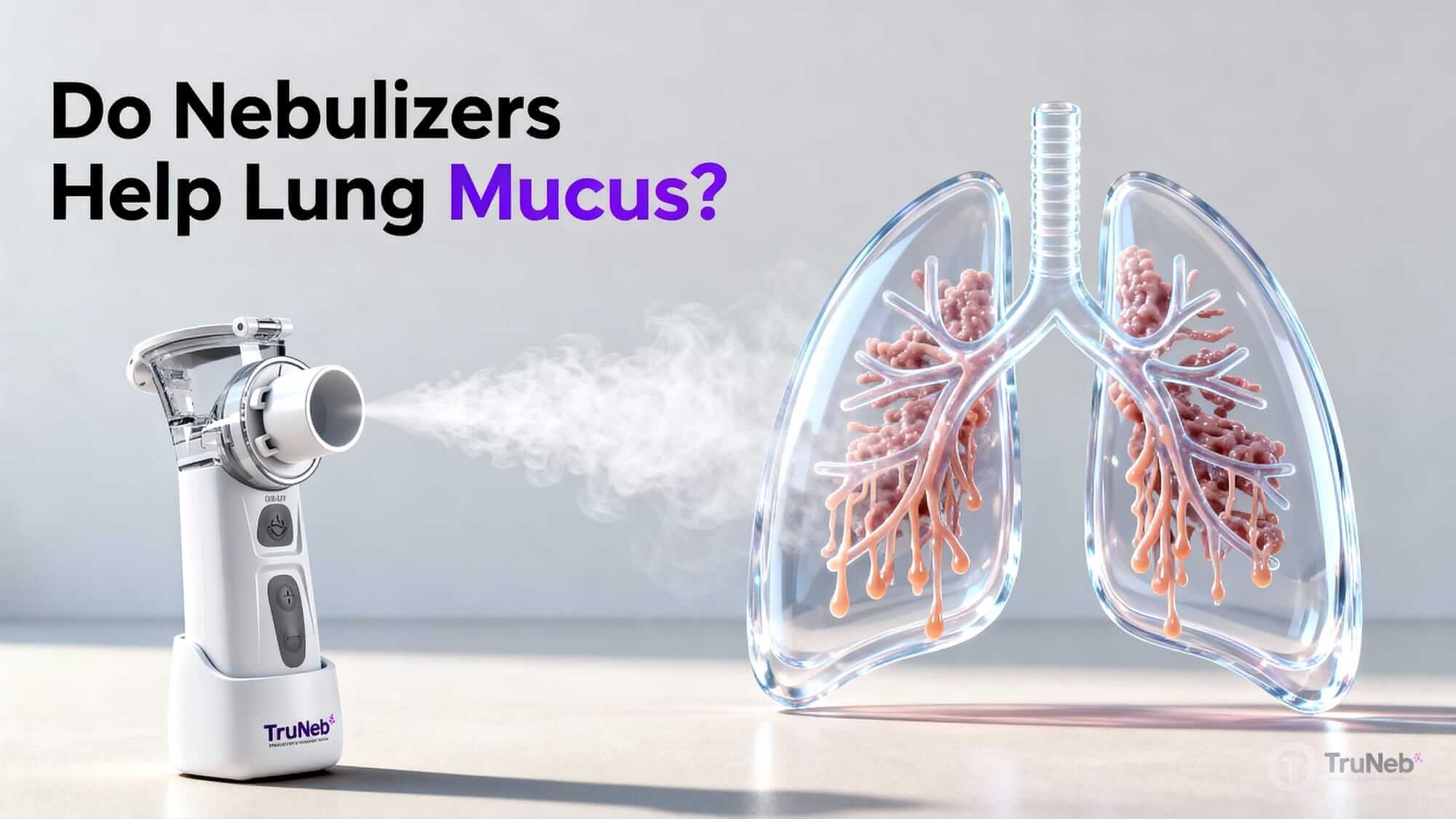

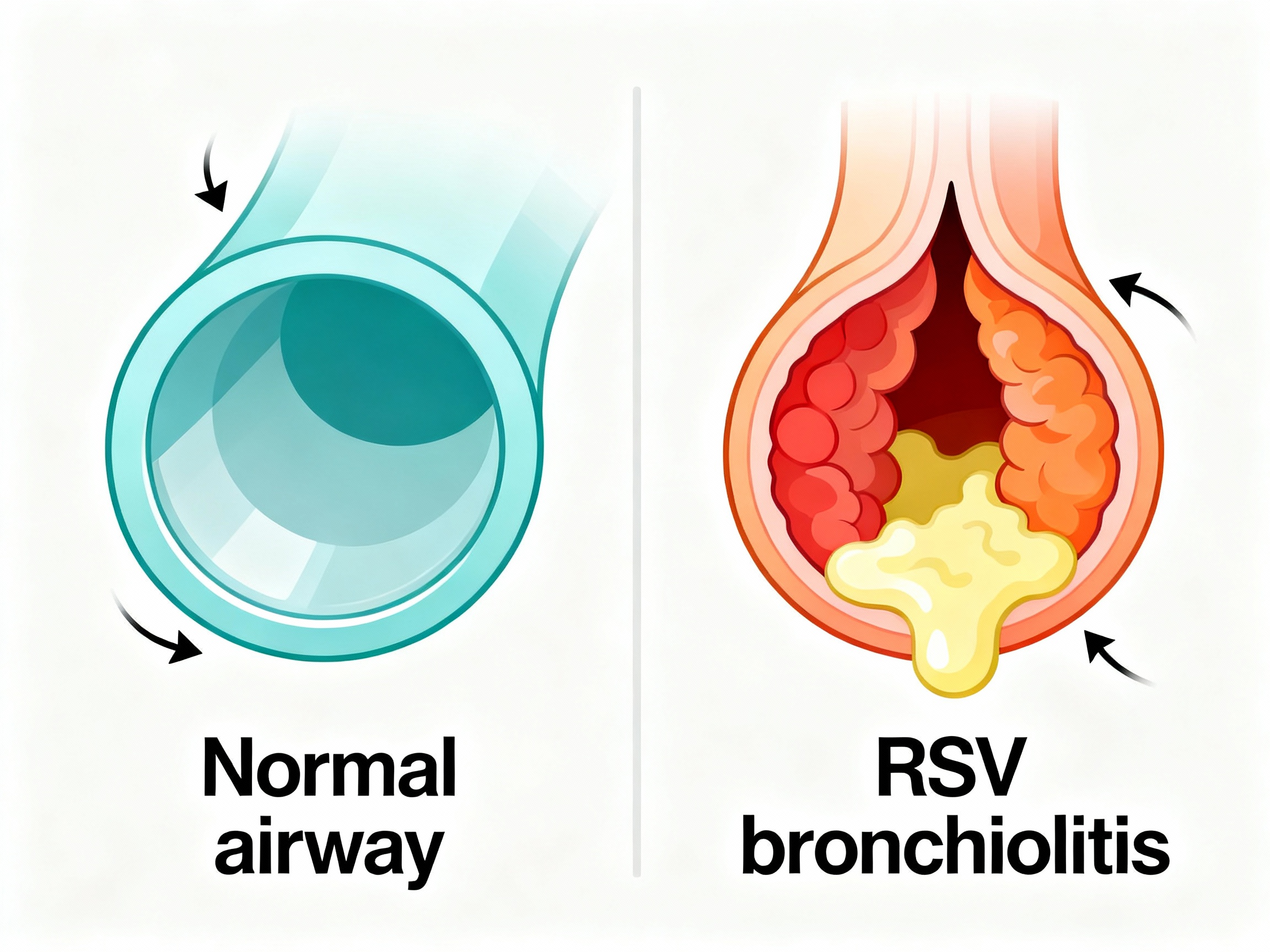

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a common virus that infects the lungs and airways. In babies and young children, it commonly causes bronchiolitis. That means the tiny breathing tubes in the lungs get swollen and filled with mucus. When those small tubes narrow, air has a harder time moving in and out. You might hear wheezing, see fast breathing, or notice your child working harder to breathe.

This wheeze is different from an asthma flare. In asthma, tight airway muscles are a big part of the problem. In RSV bronchiolitis, swelling and thick mucus are the main issues. That’s why most asthma medicines don’t help much here.

RSV sends thousands of infants to the hospital in the U.S. each year, and it can be dangerous for premature babies and those with heart or lung disease.

RSV bronchiolitis narrows tiny airways with swelling and mucus, which makes breathing hard and causes wheeze.

Nebulizers and RSV – Do They Actually Help?

For most babies with RSV bronchiolitis, nebulizer treatments like albuterol don’t help much. Major guidelines say they aren’t recommended as routine care (AAP guidelines do not recommend routine bronchodilators in bronchiolitis). Studies in infants show little to no lasting improvement in breathing, oxygen levels, or recovery time with albuterol.

Nebulizers work well for asthma because they relax tight airway muscles. In RSV bronchiolitis, the main problem is swelling and mucus, not muscle spasm, so bronchodilators don’t fix the core issue.

Nebulizer bronchodilators are generally not recommended for typical RSV bronchiolitis in infants.

Why Nebulizer Treatments Usually Don’t Work for RSV

Bronchodilators (like albuterol) relax airway muscles. In RSV bronchiolitis, the airway muscles aren’t the main problem. Swelling and sticky mucus plug the tiny tubes. It’s like trying to widen a tunnel when the tunnel is blocked by debris — you widened it, but the blockage is still there.

Trials in infants don’t show consistent, meaningful gains from bronchodilators: no clear improvement in oxygen levels, no shorter hospital stays, and no reliable change in how sick children look or feel. Unnecessary treatments can also bring side effects (fast heart rate, shakiness) and stress.

RSV wheeze comes from inflamed, mucus-filled airways, so bronchodilators don’t address the main cause.

| Condition | Primary cause of wheeze | Bronchodilators help? | First-line care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Airway muscle spasm (bronchospasm) | Usually yes | Inhalers/nebulizers as prescribed |

| RSV bronchiolitis | Swelling and mucus in tiny airways | Usually no† | Fluids, nasal saline + suction, humidified air, monitoring |

† A brief, monitored bronchodilator trial may be considered if asthma-like features are suspected; stop if no clear benefit (AAP).

When Can a Nebulizer Be Useful in RSV?

There are narrow exceptions. A doctor can try a short, supervised albuterol trial if a child has a history of wheezing, suspected asthma, or chronic lung issues (for example, a premature infant with ongoing lung disease). If there’s no clear improvement, it’s stopped.

For older kids or adults with asthma or COPD, RSV can trigger their usual bronchospasm. In those cases, their prescribed inhalers or a nebulizer can help the underlying condition, even though it doesn’t treat RSV itself.

A monitored bronchodilator trial can be considered in select patients, and it’s continued only if it clearly helps.

Nebulized Treatment Options: Albuterol, Saline, and More

Albuterol (bronchodilator)

Most studied in infants with RSV, albuterol hasn’t shown consistent, meaningful benefits. It doesn’t reliably improve oxygen, shorten hospital stay, or speed recovery. Side effects like fast heart rate can occur.

3% Hypertonic saline

This salty mist can help thin mucus. Evidence is mixed: some studies show small improvements; others do not. It’s mainly used in hospitals, not at home.

Epinephrine and steroids

Nebulized epinephrine and corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for bronchiolitis. They can offer short-term changes in some settings but haven’t shown lasting outcome benefits in typical cases.

In studies comparing saline vs albuterol for RSV, neither option consistently changed outcomes for typical bronchiolitis in infants.

In the hospital, supportive treatments like oxygen therapy and IV fluids are used if needed. Antibiotics don’t treat RSV because it’s a virus; doctors use them only if there’s a bacterial complication (like an ear infection or bacterial pneumonia).

Among nebulized options, albuterol and epinephrine aren’t routine for RSV, and hypertonic saline shows mixed results mainly in hospital care.

| Treatment | Routine for RSV? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Albuterol | No | Consider a brief, monitored trial only if asthma-like features are suspected; stop if no clear benefit. |

| Hypertonic saline (3%) | Sometimes (hospital) | Mixed evidence; mainly used in inpatient care, not at home. |

| Epinephrine | No | Not recommended for routine use. |

| Steroids | No | Not recommended unless another condition is suspected. |

| Antibiotics | No (for RSV) | Only if a bacterial complication is diagnosed. |

Sources: AAP guideline (via AAFP); Cleveland Clinic. Hypertonic saline shows mixed benefits and is typically reserved for inpatient care.

How to Help Your Child Breathe Easier During RSV (Effective Home Care)

For RSV wheezing treatment at home, supportive care helps most.

- A cool-mist humidifier can help; keep it clean daily.

- Nasal saline drops with gentle suction can clear a baby’s nose before feeds and sleep.

- Keep fluids going. Offer breastmilk, formula, or water (for older kids). Small, frequent feeds help.

- Upright positioning. Holding your child upright can ease work of breathing while awake and supervised.

- Fever comfort. For fever discomfort, age-appropriate medications can help. Always follow label instructions and ask your doctor if you’re unsure.

- No smoke exposure. Smoke irritates airways and is linked to worse illness.

- Avoid “steam inhalers.” You might see products labeled “steam inhaler” — these are NOT nebulizers and are not for breathing medications.

These steps don’t cure RSV, but they can make breathing easier while the virus runs its course.

Supportive care (humidified air, nasal saline and suction, fluids, rest) is the best at-home plan for RSV.

Warning Signs – When to Call the Doctor or Go to the ER

- Breathing trouble: very fast breaths, pulling in at the ribs or neck (retractions), nasal flaring, grunting, or pauses in breathing.

- Blue or gray color: lips, tongue, or face turning bluish.

- Dehydration: very few wet diapers (none in 8+ hours for infants), very dry mouth, no tears.

- High fever or limp/tired: in babies under 3 months, any fever ≥ 100.4°F (38°C); in older babies, very high or persistent fever; hard to wake or unusually drowsy.

- Getting worse after a week or new symptoms like ear pain.

Hospital care may include oxygen therapy or IV fluids. If you’re unsure or worried, call your child’s doctor—don’t wait. Talk to your doctor before trying a new medication.

If your child looks like they’re working to breathe or not staying hydrated, get medical help now.

Preventing RSV from Getting Worse (and Avoiding Pneumonia)

- Act early on red flags. Getting help for breathing trouble or dehydration can prevent serious complications.

- No smoke exposure. Smoke is linked to more severe RSV and lung infections.

- Hydration and rest. Keeping mucus thin and energy up helps recovery.

- Prevention tools for high-risk groups. Some infants qualify for monoclonal antibody protection during RSV season (nirsevimab for infants; palivizumab for certain high‑risk infants). There are also new RSV vaccines for older adults and pregnant people to protect newborns.

You can’t guarantee RSV won’t lead to pneumonia, but early care, hydration, and a smoke-free environment lower the risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Tap or click a question below to see the answer:

Usually no. Major pediatric guidelines do not recommend routine bronchodilators for typical RSV bronchiolitis. A brief, monitored trial may be considered only if asthma-like features are suspected, and it’s stopped if no clear benefit.

Use a cool-mist humidifier (keep it clean), nasal saline with gentle suction before feeds and sleep, offer plenty of fluids or small frequent feeds, keep your child upright when awake and supervised, give age-appropriate fever comfort as directed, and avoid all smoke exposure.

Healthy adults rarely need them. Adults with asthma or COPD should use their prescribed inhalers or a nebulizer to treat bronchospasm triggered by RSV, following their care plan.

Most people are contagious for about 3–8 days after symptoms start. Infants and those with weak immune systems can spread RSV for up to 3–4 weeks.

Symptoms usually peak around day 3–4. Most kids improve over 1–2 weeks; a cough can linger for up to about 3 weeks.

Conclusion

Most RSV infections can be managed with simple care at home: humidified air, nasal saline and suction, fluids, rest, and close watching. Nebulizers are generally not needed for typical RSV bronchiolitis in infants. If you’re worried about breathing, hydration, or a rising fever, call your child’s doctor right away.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes and isn’t a substitute for professional medical advice. Always talk with your doctor about your child’s symptoms and treatments. Call emergency services if you notice severe breathing trouble, blue lips/face, or if your child is hard to wake.