On this page

What Is Cystic Lung Disease?

Cystic lung disease is a term doctors use when your lungs have many air-filled pockets called cysts. On scans, a lung cyst looks like a round or oval space with a thin wall.

This is a group of conditions, not one single disease. Common causes include LAM, PLCH, and Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome. These can be diffuse, meaning the cysts are spread throughout both lungs. Doctors sometimes call this diffuse cystic lung disease when cysts are widespread in both lungs.

Cysts vs Bullae vs Blebs vs Cavities

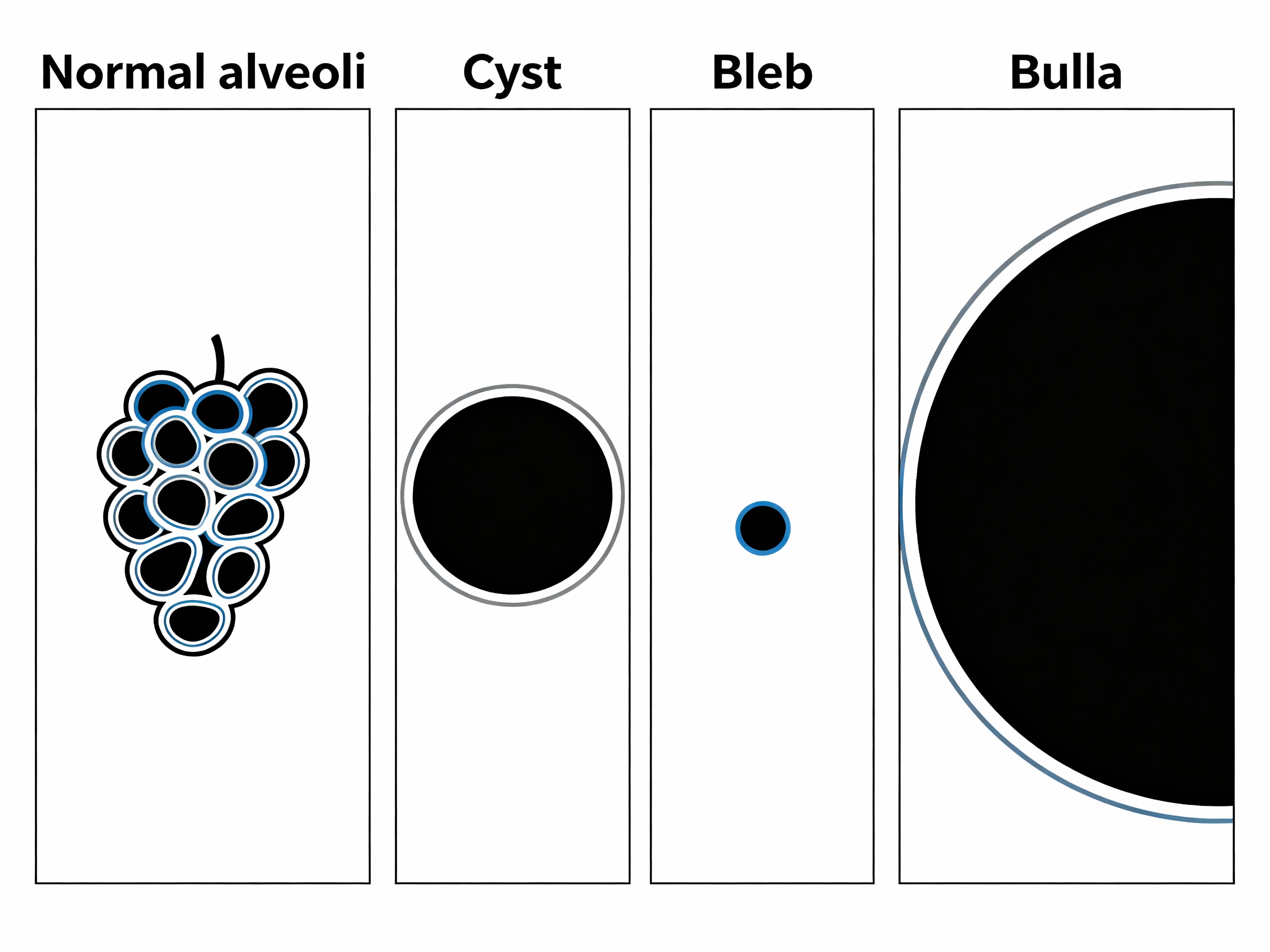

Lung cysts are different from emphysema bullae or tiny blebs, which are commonly linked to smoking and do not have the same thin, clear walls. A cavity is an air-filled space with a thicker wall, usually from infection or tissue breakdown. Honeycombing refers to stacked cyst-like spaces seen in pulmonary fibrosis and is a scarring pattern, not true cysts.

One-liner: Cystic lung disease means multiple thin-walled air spaces in the lungs caused by several different conditions.

Signs and Symptoms

Most people notice shortness of breath with activity and a dry cough. Some people have no symptoms at first and only learn about lung cysts after a CT scan for another reason.

Common signs:

- Shortness of breath, especially when walking or climbing stairs

- Dry cough

- Chest pain or sudden breathlessness from a collapsed lung (spontaneous pneumothorax)

- Reduced exercise tolerance

Clues by condition:

- LAM: chest fluid (chylothorax) and kidney angiomyolipomas sometimes appear.

- BHD: small skin bumps on the face (fibrofolliculomas) and a history of repeat collapsed lungs.

One-liner: Sudden sharp chest pain with rapid breathlessness can mean a collapsed lung, a known risk with several cystic lung diseases.

Causes and Types

Several different conditions can lead to lung cysts. Finding the exact cause matters because treatment and outlook are different. Different diseases can cause diffuse cystic lung disease, and pinpointing the cause guides treatment and outlook.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)

LAM is a rare lung disease that usually affects women in their 20s to 40s. Abnormal smooth muscle–like cells grow in the lungs and form many round, thin-walled cysts. CT scans usually show uniform cysts spread throughout both lungs with normal-looking lung between them. A lot of people have shortness of breath, and some have a collapsed lung. Some have kidney angiomyolipomas. LAM can be sporadic or occur with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).

A blood test called VEGF-D can support the diagnosis. mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus can slow decline and help stabilize lung function. Lung transplant is considered when disease is advanced.

One-liner: LAM usually shows evenly spread, thin-walled cysts in both lungs and can respond to mTOR inhibitor therapy.

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (PLCH)

PLCH is strongly linked to cigarette smoking and is most common in younger adult smokers. It usually starts as small nodules that can break down and leave behind irregular or “bizarre” shaped cysts, usually in the upper and middle lungs. About 1 in 5 have a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Quitting smoking is the key step doctors recommend, and it typically stabilizes early disease. Some patients need additional therapies if it progresses.

One-liner: In PLCH, quitting smoking is the key step and CT scans commonly show upper-lobe irregular cysts alongside nodules.

Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome (BHD)

BHD is a genetic condition caused by changes in the FLCN gene. It can cause small skin bumps (fibrofolliculomas), multiple lung cysts (often near the bases and edges of the lungs), and a higher risk of certain kidney cancers. People with BHD commonly have repeat collapsed lungs due to cyst rupture.

Genetic testing confirms the diagnosis. No medication removes the cysts. Care focuses on preventing and treating pneumothorax and on kidney screening, which your doctor will set up.

One-liner: BHD combines lung cysts, skin findings, and kidney tumor risk, with frequent repeat collapsed lungs.

Other Causes

- Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (commonly tied to autoimmune conditions like Sjögren’s)

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (HIV-related), with residual cysts after infection

- Light chain deposition disease or amyloidosis (rare)

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (can have apical blebs and cysts)

Honeycombing (seen in pulmonary fibrosis) can look like stacked cystic spaces but reflects scarring, not true cysts.

One-liner: Autoimmune, infectious, and rare deposition diseases can also leave scattered lung cysts.

At-a-Glance Comparison

| Feature | LAM | PLCH | BHD | LIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical patient | Women, 20s–40s | Young adult smokers | Any sex; inherited | Often with autoimmune disease |

| CT pattern | Diffuse, round thin-walled cysts | Upper/mid-lung irregular cysts ± nodules | Basal/subpleural cysts; varied shape | Scattered cysts with ground-glass |

| Key clues | Elevated VEGF-D; kidney angiomyolipomas | Smoking history; nodules that cavitate | Facial fibrofolliculomas; kidney tumor risk | Autoimmune markers (e.g., Sjögren's) |

| Main treatment focus | mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus); supportive | Smoking cessation; monitor; selected meds | Prevent pneumothorax; kidney screening | Immunosuppression per cause |

| Pneumothorax risk | High | Moderate | High (often recurrent) | Variable† |

† Risk varies by cyst size/location and individual factors.

Diagnosing Cystic Lung Disease

Doctors start with a high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan to look closely at the cysts. They note:

- Where the cysts are (upper vs lower lungs, central vs near the edges)

- Shape and wall thickness (round and thin vs irregular)

- Other signs (nodules, ground-glass, scarring, or fluid)

Pattern clues:

- Diffuse, round, thin-walled cysts throughout: consider LAM

- Upper-lobe irregular cysts plus nodules: consider PLCH

- Basal or subpleural oval cysts: consider BHD

- Cysts with ground-glass areas: consider LIP

Helpful tests:

- Blood VEGF-D for LAM

- Autoimmune labs if LIP is suspected

- Genetic testing for BHD (FLCN)

- Lung function tests (commonly show obstruction and/or low diffusion, and DLCO is commonly reduced)

- Lung biopsy if the picture is unclear or to confirm the exact cause

One-liner: HRCT patterns plus a few targeted tests (like VEGF-D or FLCN genetics) usually point to the right diagnosis.

Treatment and Management

Care depends on the cause and your symptoms. Your pulmonologist builds a plan around your scans, tests, and goals.

- LAM: mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus can stabilize lung function, bronchodilators can ease airflow symptoms, transplant is an option if disease becomes severe.

- PLCH: quitting smoking is the most important step, other medicines are considered in selected cases if disease progresses.

- BHD: prevent and treat pneumothorax (some will need pleurodesis after recurrences), doctors set a regular kidney screening schedule.

- LIP and others: treat the underlying cause (for example, autoimmune therapy or infection care) and support the lungs as needed.

Supportive care tools:

- Inhaled bronchodilators delivered by a portable nebulizer like TruNeb™ can help some people breathe easier during flare-ups or activity. Note: inhalers are not nebulizers and shouldn’t be used to deliver medication.

- Oxygen is used if your oxygen levels are low—your doctor will advise if it’s needed.

- Flu and pneumonia vaccines can reduce infection risk.

- Pulmonary rehab and steady, safe exercise help maintain stamina.

One-liner: Treat the cause first, then add steady lung support to protect function and prevent complications.

Prognosis and Life Expectancy

Outcomes vary by condition and how early it is found.

- LAM: people now live longer with mTOR therapy and close follow-up, and some stay stable for years.

- PLCH: about half improve or stabilize after quitting smoking, a smaller group worsens and can need advanced care.

- BHD: lung function usually stays good, the main risks are repeat pneumothorax and kidney tumors, which are managed with prevention and screening.

- LIP and others: outlook depends on the underlying disease and response to treatment.

One-liner: With earlier diagnosis and better care, a lot of people with cystic lung disease can lead active, stable lives.

Living With Cystic Lung Disease

Simple steps can lower risk and support your lungs:

- Don’t smoke or vape.

- Ask about flying in small unpressurized planes, high-altitude trips, or scuba diving if you’ve had a pneumothorax.

- Keep moving with safe, regular exercise, consider pulmonary rehab for guided training.

- Follow your screening plan (for example, kidney checks in BHD).

- Ask your doctor for an action plan for sudden chest pain or breathlessness.

- Consider using a portable nebulizer for quick bronchodilator use on busy days or travel.

- If you use a nebulizer, ask your doctor which medication to use and when.

One-liner: Small daily habits, a clear action plan, and regular check-ins can make a big difference.

Quick Safety Notes

If symptoms escalate suddenly—especially sharp chest pain and fast-rising breathlessness—treat it as an emergency.

- Chest pain or fast-rising breathlessness needs urgent care. A collapsed lung may require emergency treatment.

- Medication choices are individual. mTOR inhibitors, inhalers, or immune therapies should be guided by your specialist.

- Procedures after repeat pneumothorax. Ask about pleurodesis to reduce recurrences if you’ve had more than one collapse.

Talk to your doctor before trying a new medication.

Frequently Asked Questions

Tap or click a question below to see the answer:

No. Emphysema creates air spaces from tissue damage (bullae/blebs). Cystic lung diseases cause true thin-walled cysts from specific conditions like LAM, PLCH, or BHD.

Doctors start with high-resolution CT (HRCT) patterns and add targeted tests: VEGF-D for suspected LAM, FLCN gene testing for BHD, autoimmune labs for LIP. A lung biopsy is sometimes needed.

There’s no single cure, but many cases are manageable. Quitting smoking often stabilizes PLCH. mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus can slow LAM. Care focuses on the specific cause and preventing complications.

Having many or large cysts—especially near the lung edge—raises risk. BHD and LAM have higher pneumothorax rates. Activities with pressure changes (e.g., unpressurized flight, diving) may add risk—ask your doctor.

Only some types are inherited. Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome is genetic—close relatives may consider FLCN testing with a genetics professional. LAM and PLCH are usually not inherited, so routine family screening isn’t needed.

No. Here “cystic” refers to air-filled spaces in the lungs. Cystic fibrosis is a different genetic disease that mainly affects mucus and airways.

Most do not raise cancer risk. Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome increases the risk of certain kidney cancers, so regular kidney screening is important.

Glossary

- HRCT: High-resolution CT scan for detailed lung images.

- Cyst: Thin-walled air space in the lung seen on CT.

- Bleb/Bulla: Air spaces from emphysema, blebs are small and near the edge, bullae are larger.

- Pneumothorax: Collapsed lung from air leaking into the chest.

- VEGF-D: A blood test that can help diagnose LAM.

- mTOR inhibitor: A medicine class (e.g., sirolimus) that can slow LAM.

- Cavity: An air-filled space with a thicker wall, usually from infection or tissue breakdown—different from a thin-walled cyst.

- Honeycombing: Stacked cyst-like spaces seen in pulmonary fibrosis (scarring), not true lung cysts.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and isn’t a substitute for professional medical advice. Always talk with your doctor about your health and treatments. Call emergency services for severe or sudden symptoms.