On this page

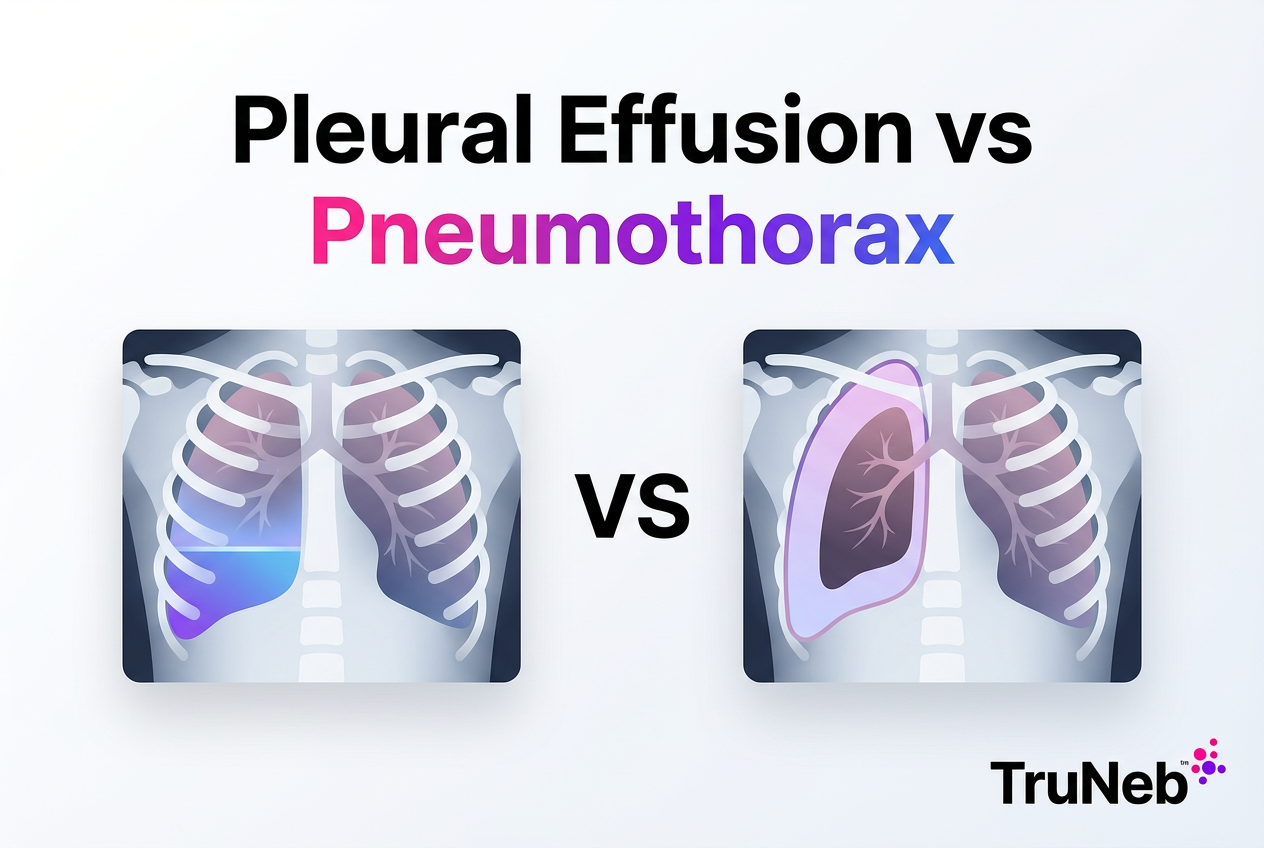

Pulmonary Edema vs Pleural Effusion: Key Differences at a Glance

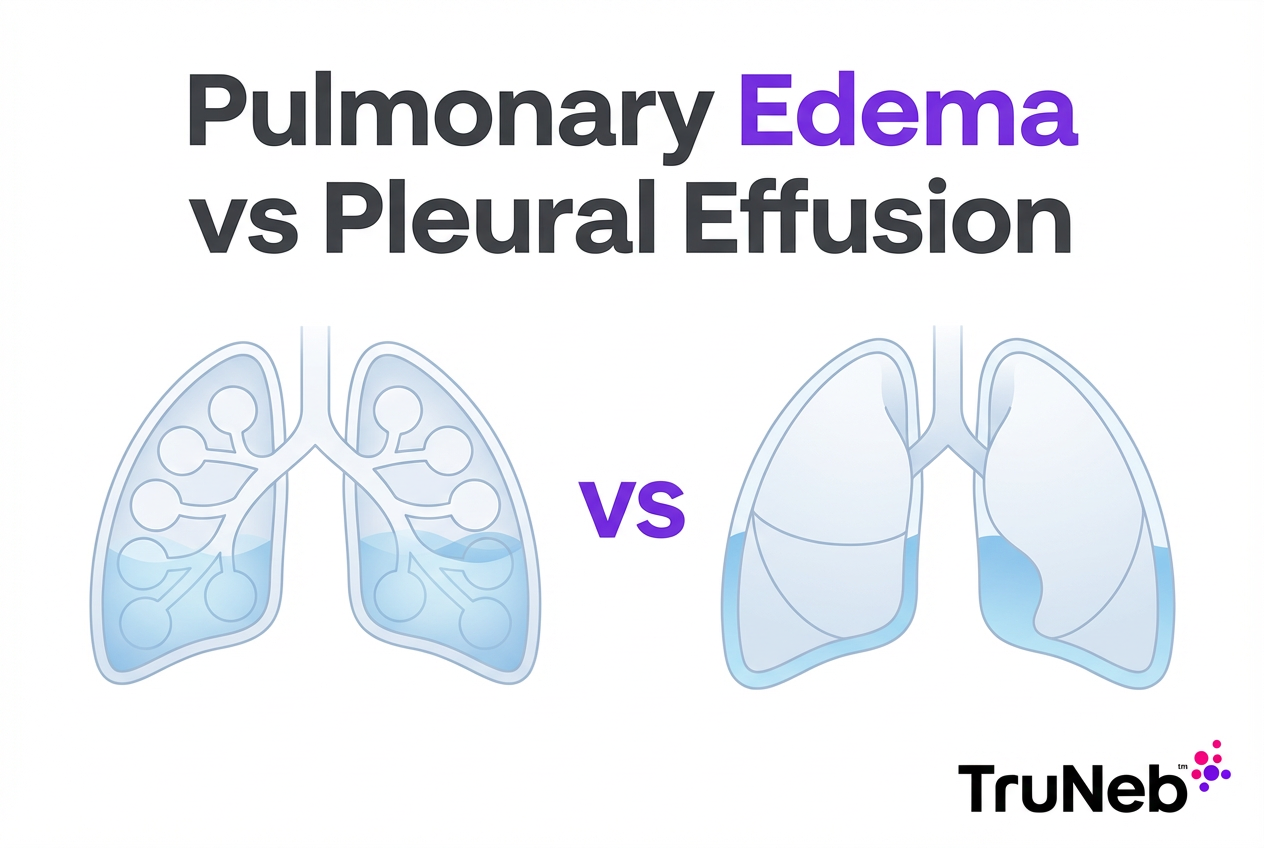

Pulmonary edema is fluid inside the lungs. Pleural effusion is fluid around the lungs.

Think of a sponge inside a thin bag: edema is the sponge soaking up water; an effusion is water filling the bag around the sponge.

The key difference between pulmonary edema and pleural effusion is where the fluid sits. Pulmonary edema is sometimes called "water in the lungs," while pleural effusion is what people mean by "fluid on the lungs."

- Location of fluid: inside the air sacs (alveoli) vs in the pleural space around the lung

- Drain with a needle? Edema: no. Effusion: yes (thoracentesis)

- Urgency: edema is usually an emergency; effusions become urgent if large or infected

Key takeaway: Fluid inside the lungs is pulmonary edema; fluid around the lungs is a pleural effusion. Edema tends to be sudden and emergent; effusions build more slowly and can be drained.

| Feature | Pulmonary Edema | Pleural Effusion |

|---|---|---|

| Where is the fluid? | Inside lung air sacs (alveoli) | In the pleural space around the lung |

| Onset | Usually sudden | Typically builds over days or weeks |

| Urgency | Medical emergency | Urgent if large, infected, or causing distress |

| Drainable with a needle | No | Yes (thoracentesis) |

| Chest X‑ray look | Diffuse lung haze, central “batwing,” Kerley lines | Fluid layering at bases, meniscus, blunted angles |

| Symptoms clue | Severe breathlessness, pink frothy sputum | Breathlessness with chest heaviness, pleuritic pain |

| Typical causes | Heart failure; heart attack; valve disease; high blood pressure | Pneumonia; cancer; heart, liver, or kidney problems |

One-liner: Inside the lungs ("water in the lungs") = pulmonary edema; around or "on" the lungs ("fluid on the lungs") = pleural effusion.

What Is Pulmonary Edema? (Fluid Inside the Lungs)

Pulmonary edema means fluid fills the tiny air sacs in your lungs (alveoli). Those air sacs normally hold air so oxygen can move into your blood. When they fill with fluid, breathing feels tight and shallow. Pulmonary edema is sometimes called "water in the lungs."

Most cases happen when pressure backs up in lung blood vessels, commonly from left‑sided heart failure. It can also happen from direct lung injury or body‑wide inflammation. Acute episodes can start suddenly and feel intense, though chronic heart failure can cause breathlessness that worsens over days or weeks.

Either way, the problem is the same: extra fluid inside the lungs blocks oxygen, so you get short of breath fast.

One-liner: Pulmonary edema is water inside the lung’s air sacs that blocks oxygen from getting into your blood.

Causes of Pulmonary Edema

The top cause is congestive heart failure. When the left side of the heart can’t pump well, pressure builds in lung vessels and fluid leaks into the air sacs.

Other causes:

- Heart attack or weakened heart muscle

- High blood pressure or heart valve disease

- Kidney failure or fluid overload

- Severe infection, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pancreatitis, or major trauma (inflammation that makes lungs leaky)

- Smoke or toxic inhalation

- High altitude (HAPE)

One-liner: Heart failure is the most common trigger, but lung injury and fluid overload can also push fluid into alveoli.

Symptoms and Signs of Pulmonary Edema

Pulmonary edema usually hits fast and feels intense.

- Severe shortness of breath, worse when lying flat

- Rapid, shallow breathing and a feeling of drowning

- Cough that can bring up pink, frothy sputum

- Wheezing, sweating, fast heartbeat, anxiety

- Bluish lips or fingertips (low oxygen)

Doctors can hear fine crackles (rales) with a stethoscope and see low oxygen levels on monitors.

⚠️ Sudden, severe breathing trouble is an emergency—call 911.

One-liner: Pink, frothy cough plus sudden air hunger points to pulmonary edema and needs emergency care.

How Pulmonary Edema Is Treated

Doctors typically treat pulmonary edema in the hospital right away to protect oxygen levels and the heart.

- Oxygen by mask or nasal cannula; sometimes CPAP/BiPAP or a ventilator

- Diuretics to pull excess fluid off through the kidneys (doctors may use medications like diuretics and, when appropriate, nitrates)

- Blood pressure support or reduction

- Treating the cause fast (heart attack care, infection control, fluid balance)

This is treated with medications and hospital care, not a drainage procedure. This isn’t a home fix.

One-liner: Care centers on oxygen, diuretics, and fixing the cause—usually in a hospital setting.

What Is Pleural Effusion? (Fluid Around the Lungs)

A pleural effusion is extra fluid in the pleural space—the thin gap between your lung and chest wall. The lung itself isn’t waterlogged; the fluid sits around it and can squeeze it, making breathing feel tight. This is what people mean when they say they have "fluid on the lungs."

Some effusions are watery (transudates, commonly from pressure or fluid overload). Others are protein‑rich (exudates, commonly from inflammation, infection, or cancer). The type helps doctors find the cause.

Small effusions sometimes cause no symptoms; large ones can greatly limit your breath.

One-liner: Pleural effusion is fluid in the space around the lung that can compress it and limit your breaths.

Causes of Pleural Effusion

Common causes include:

- Lung infections like pneumonia or tuberculosis

- Cancer in or near the chest (lung, breast, lymphoma)

- Heart failure (fluid can back up into the pleural space)

- Liver cirrhosis (fluid shifts from abdomen to chest)

- Kidney failure or very low blood protein

- Pulmonary embolism or chest trauma

A pleural effusion isn’t its own disease—it’s the result of another problem. Finding and treating the cause is key.

One-liner: Effusions happen because of another condition—often infection, cancer, or heart, liver, or kidney issues.

Symptoms and Signs of Pleural Effusion

Symptoms usually build slowly as fluid collects:

- Shortness of breath, worse with activity

- Chest heaviness or pressure

- Sharp chest pain with deep breaths or cough (pleuritic pain), especially with infection

- Dry cough

- Fever and chills if infection is the cause

On exam, doctors can find quieter breath sounds and a dull sound when tapping the chest over the fluid. Very small effusions can cause no symptoms and are found on imaging.

⚠️ If your shortness of breath quickly worsens, you develop severe chest pain, or you have a high fever with chills, contact a doctor right away or seek urgent care.

One-liner: Effusions usually cause gradual breathlessness and sometimes sharp pain with deep breaths.

How Pleural Effusion Is Treated

Treatment has two parts: removing fluid when needed and fixing the cause.

- Thoracentesis: a thin needle/catheter between the ribs to drain fluid and test it

- Chest tube for ongoing drainage if the fluid is large, thick, or infected

- Pleurodesis for recurrent malignant effusions (medicine helps the lung stick to the chest wall)

- Treat the cause (antibiotics for pneumonia, cancer therapy, diuretics for heart failure)

Small, stable effusions can be watched while the cause is treated, rather than drained immediately. Doctors drain the pleural space when it’s limiting breathing or infected.

One-liner: Effusions are often relieved by draining the pleural space and treating the underlying disease.

How Doctors Tell Them Apart (Diagnosis & Imaging)

Chest X‑ray:

- Pulmonary edema: diffuse hazy opacities in both lungs with a central “batwing” pattern or visible Kerley lines

- Pleural effusion: white area at the lung base with a curved fluid line (meniscus) and blunted costophrenic angles; large effusions can shift structures

On a chest X‑ray, doctors distinguish pulmonary edema and pleural effusion by whether the lungs look clouded throughout (edema) or fluid layers along the bases (effusion).

Physical exam:

- Edema: fine crackles (rales) as air moves through wet air sacs

- Effusion: muffled or absent breath sounds over the fluid and a dull note when the chest is tapped

Doctors also check your oxygen level with a finger sensor (pulse oximeter) to gauge severity.

Ultrasound and CT:

- Ultrasound shows pleural fluid and guides safe drainage

- CT scans clearly map fluid location and related problems

Procedures:

- Thoracentesis confirms an effusion and helps find its cause by analyzing the fluid

- You can’t draw out pulmonary edema with a needle because that fluid is inside the lung tissue

This is how doctors distinguish pulmonary edema vs pleural effusion on chest X‑ray and exam.

One-liner: On X-ray, edema clouds the lungs; an effusion pools at the base—ultrasound confirms effusions and guides drainage.

Treatment and Outlook: Pulmonary Edema vs Pleural Effusion

Pulmonary edema is a medical emergency. Doctors typically treat it in the hospital with oxygen, diuretics, breathing support when needed, and by fixing the cause. With prompt care, symptoms can improve within hours; long‑term outlook depends on your heart and lung health.

Pleural effusion care focuses on draining fluid when it limits breathing and on treating the cause. Doctors use thoracentesis or a chest tube for large or infected effusions; small, stable effusions can be watched while the underlying problem is treated. Outcomes depend on the cause—effusions may recur if the condition persists.

Neither condition is a home fix. Follow up with your doctor to manage the underlying disease and reduce the chance of it coming back.

One-liner: Edema needs emergency hospital care; effusions are drained and the cause is treated—outcomes hinge on timely care and what’s driving the fluid.

Clearing the Confusion: Fluid in Lungs vs Mucus in Airways

“Fluid in the lungs” (pulmonary edema) and “fluid around the lungs” (pleural effusion) aren’t the same as thick airway mucus. Mucus sits inside the breathing tubes in chronic lung diseases like COPD, bronchiectasis, or cystic fibrosis. Thick mucus is not the same as “water in the lungs” or “fluid on the lungs.”

For mucus, people use airway clearance and inhaled therapies.

For example, a portable mesh nebulizer such as TruNeb™ can deliver treatments that help thin mucus.

Some patients use hypertonic saline (3% or 7%) to loosen thick secretions, under medical guidance.

Nebulizers and saline help with mucus—not with pulmonary edema or pleural effusion. You can’t cough out edema or pleural fluid, and a nebulizer can’t reach those spaces. Always talk to your doctor before starting any nebulized medication or saline treatment.

One-liner: Nebulizers and hypertonic saline help thin mucus in airways; they do not treat edema inside the lungs or effusions around the lungs.

FAQs about Pulmonary Edema and Pleural Effusion

These quick answers clear up common questions about how pulmonary edema and pleural effusion overlap, how serious they are, and what treatments can and can’t do.

Tap or click a question below to see the answer:

Pulmonary edema is usually more immediately dangerous because it can drop oxygen levels fast. Large or infected effusions are serious too, but they tend to build over time and are handled with drainage and cause‑based care. Either way, if you’re suddenly short of breath, don’t wait—get emergency help.

Yes. Severe heart failure can put fluid inside the lungs (edema) and around the lungs (effusions) at the same time. Doctors treat the edema urgently and decide if an effusion needs drainage based on your breathing and test results.

A doctor’s exam and tests are needed. Pneumonia is an infection and typically brings fever and a localized spot on X‑ray. Pulmonary edema comes from heart or other pressure problems or from leaky lungs and shows a more diffuse pattern. If you have new or worsening shortness of breath, chest pain, or fever, get medical care promptly so a doctor can check for pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or other causes.

No. Nebulizers deliver medicine to open airways or thin mucus in chronic lung diseases—devices like TruNeb are designed for this kind of mucus management, not for draining fluid in or around the lungs. Edema fluid is inside the air sacs, and effusion fluid sits outside the lung. See a doctor for sudden or severe breathing trouble.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always talk with your doctor about your symptoms and treatment options.