On this page

What Oxygen Therapy Is for COPD and Why It’s Used

Oxygen use in COPD means giving you extra medical oxygen when your blood oxygen is too low. Damaged air sacs make it hard to absorb enough oxygen, so your brain, heart, and muscles don’t get what they need. Supplemental oxygen fills that gap.

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in COPD is home oxygen used for long periods each day. It’s a standard treatment for people with COPD who have chronic low oxygen (hypoxemia) at rest. When low oxygen is corrected, people think more clearly, feel less wiped out, and can do more.

It’s usually prescribed in later stages of COPD when tests confirm low oxygen; earlier stages are managed with inhalers, rehab, and other treatments. In severe COPD with low oxygen, long-term oxygen therapy in COPD is one of the few treatments shown to extend life.

Key takeaway: Long-term oxygen therapy is daily home oxygen used to correct low blood oxygen in severe COPD.

When COPD Patients Need Oxygen: Who Qualifies and How Doctors Decide

Doctors use your oxygen levels at rest to decide if you need home oxygen. Two common cutoffs are:

- SpO₂ (finger monitor) at or below 88% on room air.

- PaO₂ (arterial blood gas) at or below 55 mmHg on room air.

If your body shows stress from low oxygen (like leg swelling from right-heart strain or a high red blood cell count), oxygen can be prescribed at slightly higher numbers. Your doctor or nurse will check a pulse oximeter reading and usually confirm with an arterial blood gas (a blood test from an artery to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide). In the U.S., these values also guide insurance coverage. Criteria vary slightly by country and insurer, and your doctor looks at the whole picture, not just one reading.

Most people who qualify have very severe COPD, usually labeled Stage 4, or late Stage 3 with proven hypoxemia. Oxygen isn’t helpful if your oxygen is already in a safe range, and giving it when it isn’t needed can cause problems. After starting oxygen, expect a re-check in about 60–90 days to confirm the dose and the need. Based on testing, some people need oxygen only during sleep or with activity.

During a COPD flare-up in the hospital, oxygen is sometimes used short term under close monitoring. Here we’re focusing on long-term home use.

Key takeaway: Most people qualify for home oxygen when resting SpO₂ is 88% or lower, or PaO₂ is 55 mmHg or lower, on room air.

Benefits of Supplemental Oxygen for COPD Patients

If your oxygen is low, bringing it back to a safe range can make walking, talking, and daily tasks feel easier.

- Live longer: Using oxygen more than 15 hours a day can improve survival in severe COPD with low oxygen.

- Breathe easier: Less air hunger means you can walk farther, talk longer, and take part in rehab with better stamina.

- Think more clearly: Steady oxygen helps your brain work better. People feel less foggy and less tired.

- Sleep better: For people whose oxygen dips at night, prescribed oxygen can ease morning headaches and grogginess.

- Protect your heart: Correcting low oxygen reduces strain on the right side of your heart (cor pulmonale).

Sources: Kaiser Permanente; PubMed.

These gains apply to people who truly have low oxygen at rest. If your numbers are already safe, oxygen isn’t expected to help.

Key takeaway: Using oxygen for 15 or more hours a day can improve survival and day-to-day function in severe COPD with low oxygen.

Safe Oxygen Levels in COPD: Why 88 to 92 Percent Is the Target Range

In COPD, more oxygen is not always better—the risks of too much oxygen in COPD include CO₂ build-up. Most care teams target an oxygen saturation range of 88% to 92%. That range gives your organs enough oxygen while lowering the risk of carbon dioxide (CO₂) build-up.

Here’s why: some people with COPD retain CO₂. If oxygen is turned up too high, the brain’s drive to breathe can drop and gas exchange can worsen. CO₂ rises, causing sleepiness, morning headaches, confusion, and in severe cases, coma. This is called hypercapnia (a build-up of CO₂ in your blood). Not all COPD patients are CO₂ retainers; this target oxygen saturation range for COPD patients at risk of CO₂ retention is especially important if you’ve had hypercapnia before.

Research backs careful targets: during COPD flare-ups in the hospital, saturations kept above 92% were linked to higher death rates versus tighter control. That’s why clinicians titrate oxygen to a “just right” zone and use precise devices when needed.

Watch for: unusual drowsiness, headaches, or confusion. If you notice these, call your care team.

Key takeaway: Doctors typically target 88–92% SpO₂ in COPD to balance oxygen needs and reduce the risk of CO₂ build-up.

Home Oxygen Delivery: Concentrators, Tanks, Cannulas, and Portable Units

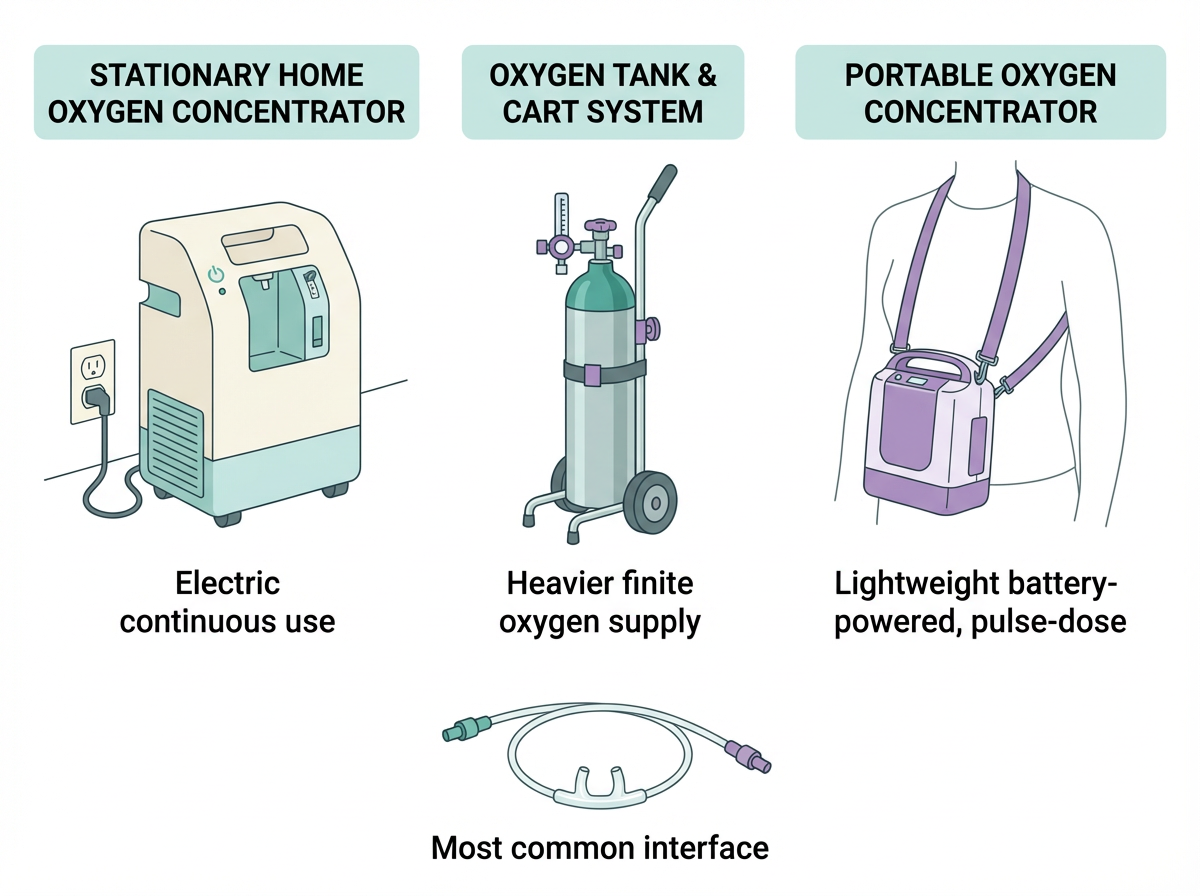

There are a few common ways to get oxygen at home. Your supplier will match your prescription and lifestyle and train you on safe setup and cleaning.

- Oxygen concentrators: Electric machines that pull oxygen from room air. Standard for continuous home use.

- Oxygen cylinders (tanks): Compressed gas in metal tanks. Handy as a backup or for short trips.

- Liquid oxygen: High-capacity systems for people who need higher flows. Less common today.

How oxygen reaches you:

- Nasal cannula: Two small prongs in your nose. Easy to talk and eat with it on—most people use this.

- Face masks: Used if higher flow is needed. In hospitals, Venturi masks deliver a precise oxygen percent.

Portable oxygen concentrators (POCs) let you go out with a small, battery-powered unit. Most models deliver oxygen in pulses when you breathe in. If your flow is high, your oxygen supplier can add a humidifier bottle to ease nasal dryness. POCs might not meet very high continuous-flow needs; your team will advise.

Comparison table: Home oxygen devices at a glance

| Device | Power/source | Flow delivery | Portability | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home oxygen concentrator | Electric outlet | Continuous flow | Stationary | Primary home oxygen supply |

| Oxygen cylinders (tanks) | Compressed gas | Continuous flow (finite supply) | Portable with cart | Backup, short trips |

| Liquid oxygen | Insulated reservoir | Continuous flow, higher capacity | Refillable portable units | Higher flow needs with mobility |

| Portable oxygen concentrator (POC) | Battery + charger | Pulse dose, some units offer limited continuous flow | Lightweight, carryable | Outings, travel, ambulation |

Note: Pulse dose delivers oxygen when you inhale; continuous flow is a constant stream. Check with your clinician or supplier to make sure a device meets your prescription.

Key takeaway: Most people use a home concentrator with a nasal cannula and add a portable option for outings.

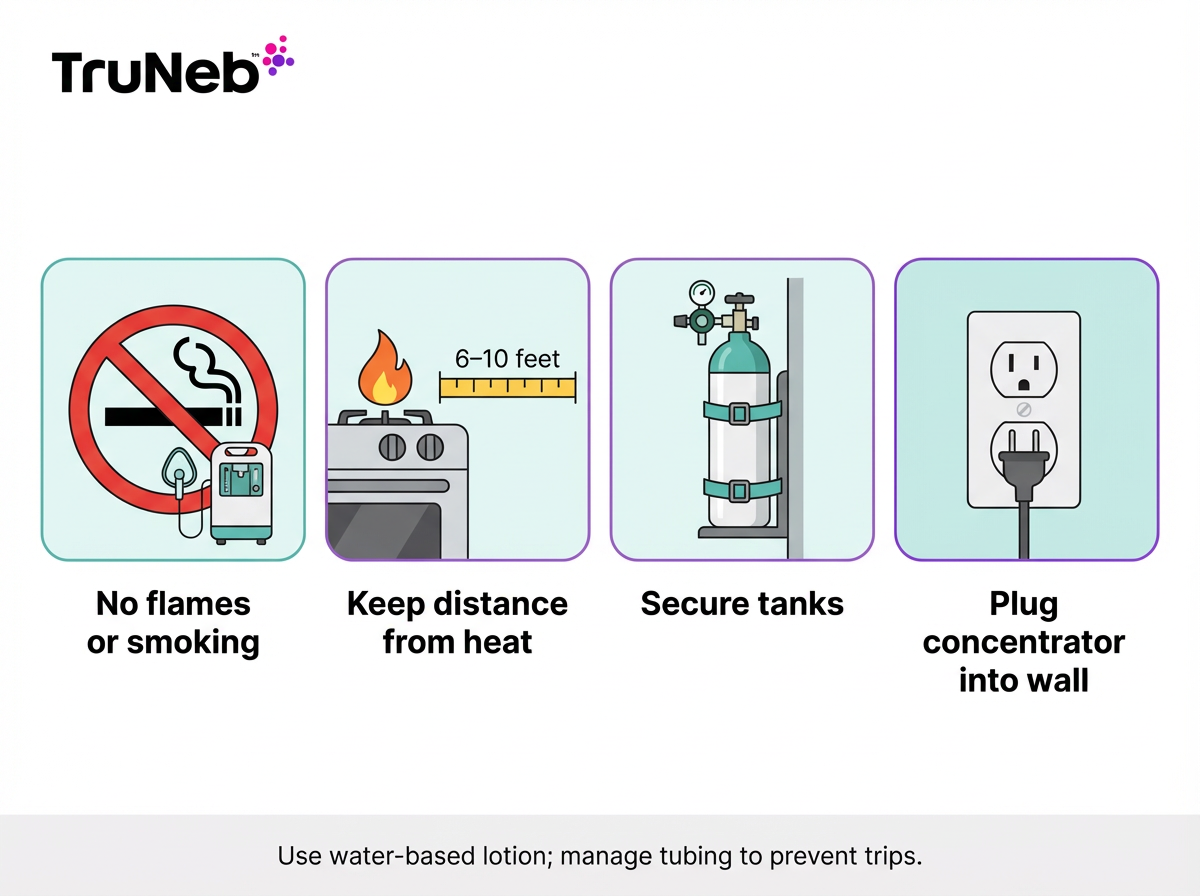

Home Oxygen Safety Tips for COPD

Oxygen helps you breathe. It also makes fires burn faster. These home oxygen safety tips for COPD can keep you safe.

Do this:

- Keep oxygen 6–10 feet away from open flames, gas stoves, candles, and space heaters.

- Post “No Smoking – Oxygen in Use” signs. Ask guests to follow them.

- Plug concentrators straight into a wall outlet. Check smoke detectors and keep a fire extinguisher nearby.

- Secure tanks upright so they can’t tip. Store them away from heat.

- Manage tubing so you won’t trip. Check for kinks.

- Clean cannulas and masks as directed. Ask about humidification if your nose gets dry.

- Have a backup plan: extra tank for outages and your supplier’s 24/7 phone number.

Avoid this:

- No smoking or vaping anywhere near oxygen.

- No oil-based lotions, petroleum jelly, or aerosol sprays on the face around oxygen. Use water-based products.

⚠️ Never smoke or let anyone else smoke around oxygen—fires start and spread much faster when extra oxygen is in the air.

Travel is possible with planning. Airlines usually allow portable concentrators with advance notice. For car trips, plan ahead—bring extra supplies and secure your equipment in the car so it can’t tip or roll.

Safety note: Don’t change your oxygen flow or hours without medical guidance. Use it the way your doctor prescribed. If symptoms don’t improve or you notice new problems while on oxygen, contact your doctor. ⚠️ Get emergency help right away if you have severe trouble breathing, chest pain, blue lips or fingers, or confusion that gets worse.

Key takeaway: Keep oxygen far from flames, follow your prescribed settings, and set up a simple backup plan.

Combining Oxygen Therapy with Medications, Nebulizers, and Saline

Oxygen raises low blood oxygen. Medicines open airways and thin mucus. Most people on oxygen still use inhaled bronchodilators and other COPD meds as prescribed. Oxygen doesn’t replace inhalers, nebulizers, or pulmonary rehab; they work together.

Nebulizer treatments can help if inhalers are hard to use. A portable mesh nebulizer, like the TruNeb™ Portable Mesh Nebulizer, turns liquid medicine into a fine mist you breathe in over a few minutes. You can use a nebulizer while wearing your nasal cannula. Some setups connect a nebulizer to an oxygen source when your clinician advises it. Only use connections and settings provided by your doctor or equipment supplier—don’t try to modify equipment on your own.

If you struggle with thick mucus every day, your clinician might discuss saline nebulization. Hypertonic saline (3% or 7%) can draw water into the airways and thin thick sputum so it’s easier to cough out. TruNeb offers 3% and 7% hypertonic saline ampoules for use with its portable mesh nebulizer when prescribed. Evidence in COPD is still evolving, so it isn’t for everyone, but targeted airway clearance can help some people.

Pulmonary rehab pairs well with oxygen and inhaled meds. Training your body to move more efficiently can lift your stamina and confidence.

Important: Talk to your doctor before trying a new medication or saline. Never start, stop, or change treatments on your own.

Key takeaway: Oxygen treats low O₂; inhaled meds, nebulizers, and hypertonic saline can help open airways and clear mucus.

FAQs: Oxygen Use in COPD

Tap or click a question below to see the answer:

It’s usually prescribed in very severe COPD (usually Stage 4) or late Stage 3 when tests show low oxygen at rest. See “When COPD Patients Need Oxygen” above for the exact test numbers.

Long-term levels below about 88% are considered unsafe because organs don’t get enough oxygen. Pushing saturations too high with supplemental oxygen can increase the risk of CO₂ build-up in some people; clinicians typically aim for 88–92%.

Yes. Too much oxygen can lead to CO₂ retention (hypercapnia), causing sleepiness, headaches, and confusion. This is why doctors set a target range; ask your clinician if you’re unsure about your settings.

No. Oxygen doesn’t make your lungs lazy—it supports your body when your lungs can’t supply enough oxygen. If your condition improves, your doctor can reassess your need.

Doctors commonly prescribe 15 or more hours a day for the best benefits; some people need it all day and night. See the benefits section above for why time on oxygen matters.

Yes. Portable oxygen concentrators make trips possible, including flights with airline approval. Lots of people on oxygen still travel—plan ahead, bring extra supplies, and secure your equipment in the car so it can’t tip or roll.

Key takeaway: Oxygen therapy is usually reserved for advanced COPD with low oxygen levels, and your doctor adjusts the dose and hours to fit your specific needs.

Note: Talk to your doctor before trying a new medication. Never change your oxygen settings without medical guidance.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always talk with your doctor about your symptoms, test results, and treatment options, including oxygen use.