On this page

How High Altitude Affects Breathing in COPD

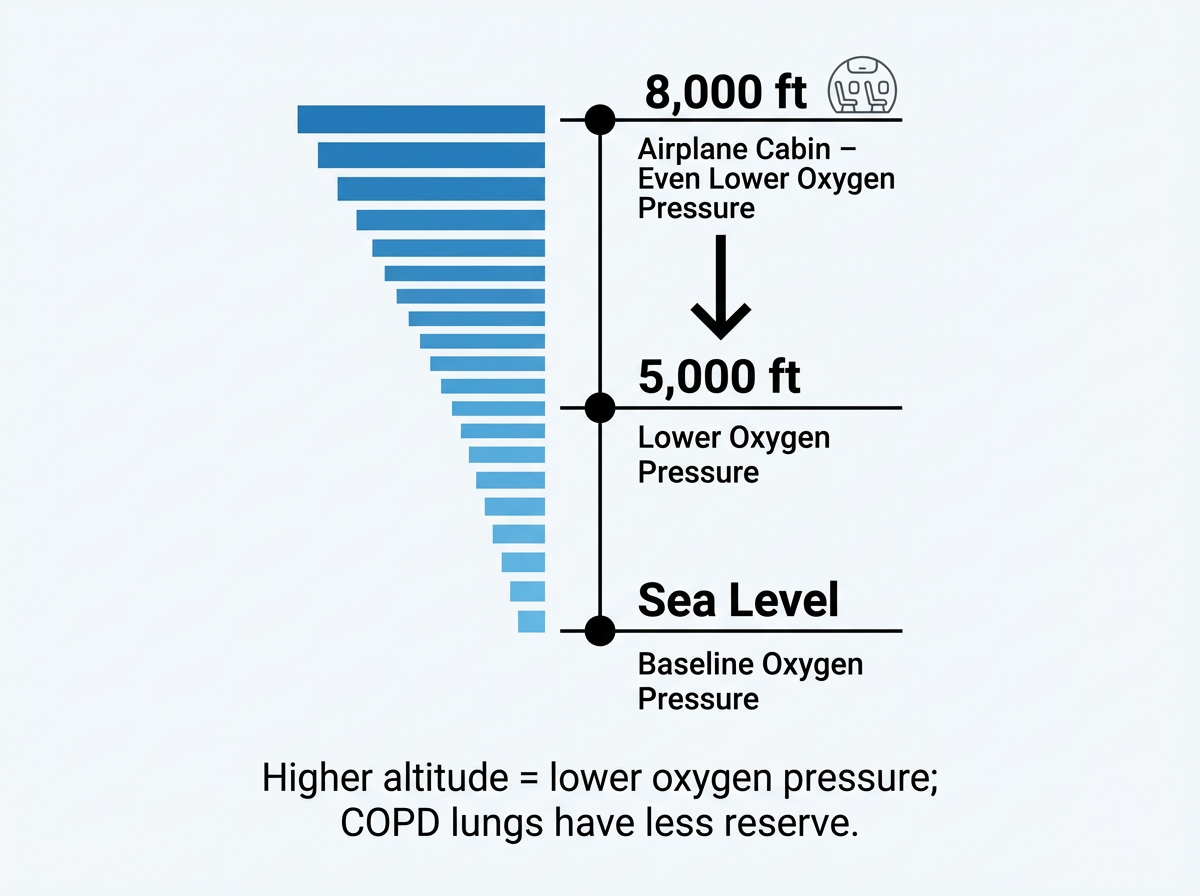

High altitude means lower air pressure, so each breath delivers less oxygen than at sea level. If you have COPD, that "thin air" feels harder because your lungs have less reserve.

Think of altitude like turning down an oxygen dial. Around 5,000 feet (about 1,500 m) and higher, your body has to work more for the same oxygen. Doctors usually consider "high altitude" to start around 5,000 feet (about 1,500 meters). Lots of people notice deeper or faster breathing, a quick pulse, and earlier fatigue. With COPD, mild activity can trigger shortness of breath sooner.

Oxygen saturation (SpO2) is the percentage of oxygen in your blood; with COPD it can fall more quickly at altitude than at sea level.

What this looks like day to day:

- Hills or stairs feel steeper.

- You might need more rest between activities.

- Headaches or poor sleep can show up the first days at altitude.

- If you have COPD, even small climbs can feel steeper.

Quick take: High altitude lowers oxygen pressure, so people with COPD can desaturate and feel short of breath much sooner than at sea level.

Altitude Risks for COPD: Hypoxemia and Altitude Sickness

The main risk at altitude is hypoxemia (low blood oxygen). When oxygen drops, you can feel weak, dizzy, or confused. Your heart and lungs also face more strain.

Risks to know:

- Bronchospasm: cold, dry air can tighten airways and worsen wheeze.

- Dynamic hyperinflation: faster breathing can trap air and raise the work of breathing.

- Pulmonary hypertension spike: low oxygen narrows lung blood vessels and can strain the right heart.

- Sleep trouble and fatigue: oxygen can dip more at night.

Altitude sickness (acute mountain sickness, AMS) can affect anyone, and COPD can make it show up sooner and feel worse. In healthy travelers, AMS typically starts above about 8,000–9,000 feet, but with COPD symptoms and AMS can start lower, even around 5,000 feet. Common AMS symptoms include headache, dizziness, nausea, tiredness, and trouble sleeping. If these symptoms start, rest and don’t go any higher until they improve. If they don’t ease up, contact a doctor or local clinic.

Serious but less common problems:

- High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE): fluid in the lungs at altitude. This is an emergency. Signs include severe shortness of breath at rest, cough, and a fast heartbeat.

- Worsening confusion, staggering, or blue lips/fingernails (cyanosis) signal dangerous hypoxemia.

Air travel counts as altitude exposure because the cabin feels like being on a mountain. People with COPD can see their oxygen levels drop during flights. Planning ahead can help.

Quick take: Hypoxemia is the core altitude risk in COPD, and AMS symptoms can appear at lower elevations than in healthy people with COPD.

Preparing for High-Altitude Travel with COPD: A Simple Checklist

Good prep can make altitude trips safer and less stressful.

Consult your doctor and get checked

- It’s a good idea to book a pre‑trip visit with your pulmonologist.

- Ask about a high‑altitude or fit‑to‑fly assessment (hypoxic challenge test) to see if you’ll need oxygen in the air or at your destination. This usually involves breathing low‑oxygen air while your doctor checks your oxygen levels, doing simple breathing tests, and sometimes a walking test.

- Review recent flare-ups and all inhalers/nebulized meds.

- Your doctor can adjust your treatment and, in some cases, consider preventive medicines for AMS. These medicines need a prescription and aren’t right for everyone.

Plan for oxygen (especially for flights)

- Airplane cabins feel like 6,000–8,000 ft. When flying with COPD, you might still need oxygen even if you’re fine at sea level.

- If prescribed, arrange in‑flight oxygen or an approved portable oxygen concentrator in advance. Airlines usually require paperwork and device approval (your airline can explain their process).

Ascend gradually and ease in

- When possible, gain elevation in steps and take a rest day on arrival.

- Plan gentler activity, with breaks, especially on the first 1–2 days. Doctors usually recommend avoiding heavy exertion, alcohol, and sleep aids that can depress breathing early at altitude.

- Trips higher than about 6,500 feet (~2,000 m) deserve extra caution if you have moderate–severe COPD, but your doctor’s advice should guide the call.

Pack a COPD travel toolkit

- All regular meds: daily inhalers, rescue inhaler, and any nebulizer solutions.

- Portable mesh nebulizer: a compact device like the TruNeb™ Portable Mesh Nebulizer lets you take nebulized treatments on the go without a bulky machine.

- Pulse oximeter to check oxygen levels.

- Extra oxygen batteries/supplies if you use a concentrator.

- Peak flow meter if you track airflow changes.

- Water bottle and warm layers.

- Emergency plan: your doctor’s contact, local urgent care info, and insurance details.

Altitude contexts and what to plan

| Context | Approx. elevation | What it means for oxygen | What to plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airline cabin | ~6,000–8,000 ft | Lower oxygen pressure; SpO2 can drop compared with sea level. | Ask about in‑flight oxygen or an approved portable oxygen concentrator; arrange paperwork early. |

| Mountain town | ~5,000–7,000 ft | Earlier shortness of breath, fatigue, and sleep changes possible. | Go up gradually, plan a light first day, discuss oxygen needs with your doctor. |

| High mountain | ≥9,000 ft | Greater hypoxemia risk; AMS more likely for everyone. | Ascend slowly, consider preventive strategies with your doctor, be ready to descend if symptoms worsen. |

Notes: Elevations are approximate. Follow your doctor’s plan for testing and oxygen.

Quick take: Plan with your pulmonologist, arrange oxygen early, ascend slowly, and carry a simple COPD travel kit to stay safe at altitude.

Coping at Altitude: Staying Safe and Managing Symptoms

Once you arrive, take things slowly and pay attention to how your body feels. Small habits help a lot.

Keep airways happy

- Drink water regularly; air at altitude is usually dry, and hydration helps thin mucus.

- Use layers and a scarf or mask outdoors to warm the air you breathe and calm airways.

- If you use nebulized meds, some people also use sterile saline by nebulizer to keep airways moist. With your clinician’s guidance, a portable mesh nebulizer (like TruNeb) with 3% or 7% hypertonic saline can help loosen thick mucus in dry conditions. This isn’t right for everyone, so your doctor should tell you if it fits your plan. Only use hypertonic saline solutions your doctor has prescribed or approved.

- If you see boxes labeled "steam inhaler" in stores, those are not for breathing medications and don’t replace your nebulizer or oxygen.

Pace your day

- Plan gentler activity, with breaks, especially on the first 1–2 days.

- A pulse oximeter can help you spot-check your oxygen level. Ask your doctor what range to aim for.

- If oxygen was prescribed, use it as directed during activity and sleep.

Protect sleep

- People tend to breathe less steadily at altitude, and oxygen can dip more at night. If your doctor recommends nighttime oxygen or other steps, follow that plan. Avoid alcohol late in the day.

⚠️ When to seek help

- Severe headache with nausea or vomiting

- Confusion, trouble walking straight, or fainting

- Chest pain, pounding heartbeat, or blue lips/fingernails

- Worsening breathlessness at rest that doesn’t improve with oxygen and rest

⚠️ If you notice severe shortness of breath at rest, chest pain, confusion, or blue lips/fingernails at altitude, use your prescribed oxygen if available and seek emergency medical care right away (911 in the U.S. or your local number). If you can, go to a lower altitude.

⚠️ Talk to your doctor promptly if your breathing or oxygen levels stay worse at altitude, or if you’re thinking about changing your usual treatment. Plan with your doctor, monitor your symptoms, and don’t push through red flags.

Quick take: Hydration, gentle pacing, warmed air, and doctor‑guided nebulized saline can make breathing at altitude more comfortable with COPD.

Living at High Altitude with COPD: Long-Term Impacts

Staying at altitude full time is different from a short trip. Research links long-term high-altitude living in COPD with lower exercise capacity and more frequent oxygen dips during activity.

What studies suggest

Above roughly 4,000–5,000 ft, people with COPD tend to walk shorter distances on standardized tests and desaturate more during exertion than those near sea level.

Reviews also note higher COPD mortality at altitude, likely due to chronic low oxygen and heart–lung strain over time. Altitude itself doesn’t cause COPD, but it can make daily life harder if lung function is limited.

Practical takeaways

- If symptoms are getting worse at altitude, ask your doctor if moving lower could help. Doctors sometimes recommend relocating to a lower elevation if COPD is worsening despite treatment.

- If you stay, expect close follow-up: long-term oxygen therapy (sometimes at night), heart checks, and monitoring for thickened blood (polycythemia).

- Keep up pulmonary rehab habits and your treatment plan.

Quick take: Long-term altitude can mean lower exercise capacity and more oxygen drops in COPD.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always talk with your doctor about your COPD, your travel plans, and any treatments you’re considering.